What Ingredients Are Needed To Brew Beer?

Water

Importance of Water in Brewing

Water Composition

The composition of water, specifically its mineral content, can significantly influence the brewing process and the final flavor profile of the beer. Here are the primary minerals found in brewing water and their effects:

- Calcium (Ca²⁺): This mineral aids enzyme activity in the mashing process, helping to break down starch into fermentable sugars. Calcium also improves yeast health, contributes to beer stability, and enhances the clarity and flavor profile of the beer.

- Magnesium (Mg²⁺): While less critical than calcium, magnesium also acts as a cofactor for enzymes during fermentation. It should be present in lower concentrations, as high levels can impart a bitter taste.

- Sodium (Na⁺): Sodium can enhance the sweetness and fullness of the beer’s flavor. However, excessive sodium levels can make the beer taste salty and undesirable.

- Sulfate (SO₄²⁻): Sulfates accentuate hop bitterness and dryness, making them particularly important in hoppy beer styles like IPAs.

- Chloride (Cl⁻): Chlorides contribute to the perception of malt sweetness and fullness, balancing the bitterness imparted by sulfates.

- Bicarbonate (HCO₃⁻): Bicarbonates affect the mash pH and can help balance the acidity from dark malts. However, high bicarbonate levels can lead to harsh, alkaline flavors.

Adjusting Water for Brewing

Brewers often adjust their water profile to match the desired beer style they are creating. This can involve adding minerals to achieve a specific profile or using reverse osmosis (RO) water to start with a blank slate. Here are some common adjustments and considerations:

- Water Profiles for Different Beer Styles: Different beer styles benefit from specific water profiles. For example, Pilsners and other light lagers typically require soft water with low mineral content. In contrast, hoppy beers like IPAs benefit from a higher sulfate-to-chloride ratio to enhance bitterness. Dark beers like porters and stouts often require higher bicarbonate levels to balance the acidity of roasted malts.

- Mineral Additions: Brewers can add brewing salts to their water to achieve the desired mineral content. Common salts include gypsum (calcium sulfate) for adding calcium and sulfates, calcium chloride for increasing calcium and chloride, and Epsom salts (magnesium sulfate) for adding magnesium and sulfates.

- Water Treatment Methods: In addition to adding minerals, brewers can use various treatment methods to adjust their water. These include carbon filtration to remove chlorine and chloramine, acid additions to lower pH, and boiling or dilution with RO water to reduce bicarbonate levels.

- Measuring and Monitoring: Successful water adjustment requires careful measurement and monitoring. Brewers often use water testing kits or send samples to labs to determine the exact mineral content of their source water. They then use brewing software or calculators to make precise adjustments based on the desired beer style.

Malt

Role of Malt in Brewing

Types of Malt

Base Malts

Base malts make up the bulk of the grain bill and provide the majority of the fermentable sugars. They are lightly dried to preserve their enzyme activity, which helps convert starch into sugars during the mashing process. Common base malts include:

- Pilsner Malt: Known for its light color and clean, sweet flavor, Pilsner Malt is a staple in lagers and many other beer styles.

- Pale Malt: Slightly darker than Pilsner malt, pale malt offers a balanced malt flavor suitable for a wide range of beer styles, including ales and IPAs.

- Maris Otter: A traditional British malt with a rich, biscuity flavor, often used in English-style ales.

Specialty Malts

Specialty malts are used in smaller quantities to add specific flavors, colors, and aromas to the beer. These malts undergo various degrees of kilning, roasting, or caramelization, which develop distinct characteristics. Key types of specialty malts include:

- Crystal/Caramel Malt: Adds sweetness, color, and caramel flavors. These malts are available in a range of color ratings (Lovibond or EBC), from light caramel to dark, toffee-like flavors.

- Chocolate Malt: Imparts deep brown color and rich, roasted flavors reminiscent of coffee or dark chocolate. Commonly used in porters and stouts.

- Black Malt: Provides intense color and robust roasted flavors, often used sparingly to achieve a dark color and burnt taste.

- Munich Malt: Adds malty sweetness and body, with a toasty flavor, often used in darker lagers and ales.

The Malting Process

Steeping

Germination

Kilning

Hops

Importance of Hops in Brewing

Components of Hops

Alpha Acids

Beta Acids

Essential Oils

Essential oils in hops are responsible for the wide range of flavors and aromas they impart to beer. These volatile compounds are released during the brewing process, especially when hops are added late in the boil or during fermentation. The primary essential oils found in hops include:

- Myrcene: Contributes to floral, citrus, and herbal aromas.

- Humulene: Adds earthy, woody, and spicy notes.

- Caryophyllene: Provides spicy, woody, and peppery characteristics.

- Farnesene: Imparts floral and green, fresh aromas.

Types of Hops

Bittering Hops

Bittering hops are high in alpha acids and are primarily used to add bitterness to the beer. They are typically added early in the boil to maximize the isomerization of alpha acids. Common bittering hop varieties include:

- Magnum: Known for its clean bitterness and high alpha acid content.

- Warrior: Offers a smooth, balanced bitterness with a high alpha acid percentage.

- Chinook: Provides a strong, piney bitterness with a high alpha acid content.

Aroma Hops

Aroma hops are lower in alpha acids but rich in essential oils, making them ideal for adding flavor and aroma to beer. They are usually added late in the boil or during fermentation. Popular aroma hop varieties include:

- Cascade: Known for its floral, citrus, and grapefruit aromas.

- Saaz: A traditional noble hop with delicate, earthy, and herbal notes.

- Hallertau: Offers mild, spicy, and floral aromas, often used in lagers.

Dual-Purpose Hops

Dual-purpose hops can be used for both bittering and aroma, offering a balance of alpha acids and essential oils. These hops are versatile and can be added at various stages of the brewing process. Common dual-purpose hop varieties include:

- Centennial: Provides balanced bitterness with floral and citrus aromas.

- Amarillo: Known for its orange-citrus and floral characteristics, suitable for both bittering and aroma.

- Simcoe: Offers piney, earthy, and fruity aromas, with good bittering potential.

Hop Additions and Timing

First Wort Hopping

Boil Additions

Hops added during the boil contribute varying degrees of bitterness, flavor, and aroma depending on the timing of the addition:

- Bittering Addition (60 minutes or more): Hops added at the start of the boil primarily contribute to bitterness, as the extended boil time allows for maximum isomerization of alpha acids.

- Flavor Addition (15-30 minutes): Hops added during the middle of the boil contribute both bitterness and flavor, with a balance between isomerization and essential oil retention.

- Aroma Addition (0-15 minutes): Hops added near the end of the boil or at flameout primarily contribute aroma and flavor, as the short boil time preserves the volatile essential oils.

Dry Hopping

Yeast

Role of Yeast in Brewing

Types of Yeast

Ale Yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae)

Ale yeast is a top-fermenting yeast, meaning it ferments at the top of the fermentation vessel. It operates best at warmer temperatures, typically between 15-24°C (59-75°F). Ale yeast tends to produce more esters and phenols, resulting in a wide range of fruity and spicy flavors. This yeast type is commonly used in a variety of ale styles, including pale ales, IPAs, stouts, and Belgian ales.

- American Ale Yeast: Known for clean fermentation with subtle fruity esters, suitable for a wide range of American ales.

- English Ale Yeast: Produces more pronounced esters and sometimes diacetyl, contributing to the characteristic flavor of English ales.

- Belgian Ale Yeast: Offers complex profiles with high ester and phenol production, resulting in fruity and spicy flavors typical of Belgian styles.

Lager Yeast (Saccharomyces pastorianus)

Lager yeast is a bottom-fermenting yeast, fermenting at the bottom of the vessel. It prefers cooler fermentation temperatures, typically between 7-13°C (45-55°F). Lager yeast ferments more slowly and cleanly, producing fewer esters and phenols, which results in a crisp, clean flavor profile. This yeast type is used for various lager styles, including Pilsners, Helles, Märzens, and Bocks.

- Pilsner Lager Yeast: Known for its clean, crisp finish with minimal ester production, ideal for light lagers.

- Munich Lager Yeast: Produces slightly more malt-forward flavors, suitable for darker lagers like Dunkels and Bocks.

- Vienna Lager Yeast: Balances malt sweetness with a clean finish, perfect for Vienna lagers and Märzens.

Yeast Management

Pitching Rate

Aeration

Fermentation Temperature

Yeast Nutrients

Yeast Harvesting and Reuse

Yeast Strain Selection

Adjuncts and Additives

Adjuncts

Grains

- Corn: Corn is commonly used in American lagers to lighten the body and color of the beer without adding significant flavor. It also increases fermentable sugars, which can boost the alcohol content.

- Rice: Similar to corn, rice is used to produce lighter-bodied beers with a clean, crisp finish. It is a staple in many commercial light lagers.

- Wheat: Wheat is used in various beer styles, such as wheat beers, to enhance the body and head retention. It contributes a subtle, bready flavor and a slightly hazy appearance.

- Rye: Rye adds a spicy, dry flavor and can increase the complexity of the beer. It is often used in rye IPAs and rye pale ales.

- Oats: Oats contribute to a smooth, creamy mouthfeel and are commonly used in stouts and porters to add body and silkiness.

Sugars

- Cane Sugar: Cane sugar is highly fermentable and can be used to increase the alcohol content without adding significant flavor or body. It is often used in Belgian-style ales and high-gravity beers.

- Honey: Honey adds fermentable sugars and subtle floral and sweet flavors. It can also contribute to the beer’s aroma.

- Molasses: Molasses imparts a rich, dark sweetness and can add complexity to darker beer styles like stouts and porters.

- Candi Sugar: Commonly used in Belgian ales, candi sugar comes in various colors and adds distinct flavors ranging from light caramel to deep, rich toffee.

Flavor Additives

Fruits

- Citrus (Orange, Lemon, Lime): Citrus fruits add bright, zesty flavors and are commonly used in wheat beers, IPAs, and Belgian-style ales.

- Berries (Raspberries, Blueberries, Cherries): Berries provide vibrant color and fruity flavors, often used in fruit beers and lambics.

- Stone Fruits (Peaches, Apricots, Plums): Stone fruits contribute sweet, juicy flavors and aromas, enhancing the complexity of various beer styles.

Spices and Herbs

- Coriander: Coriander adds a citrusy, spicy flavor and is a traditional ingredient in Belgian witbiers.

- Cinnamon: Cinnamon imparts warm, sweet, and spicy notes, often used in winter ales and spiced beers.

- Vanilla: Vanilla adds a smooth, creamy sweetness and is commonly used in stouts, porters, and barrel-aged beers.

- Ginger: Ginger provides a sharp, zesty flavor with a hint of heat, suitable for spiced ales and holiday beers.

- Peppercorns: Peppercorns add a subtle heat and spiciness, enhancing the complexity of various beer styles.

Clarifying Agents

Types of Clarifying Agents

- Irish Moss: A type of red seaweed added during the last 10-15 minutes of the boil. Irish moss helps coagulate proteins, which then settle out of the wort during cooling.

- Whirlfloc Tablets: A refined form of Irish moss, these tablets are convenient and effective at promoting protein coagulation and improving wort clarity.

- Gelatin: Gelatin finings are added to the cold beer after fermentation. They bind with suspended particles, causing them to settle to the bottom of the fermenter.

- Isinglass: Made from fish swim bladders, isinglass is added to the finished beer to help clear yeast and other particulates.

- Polyclar (PVPP): A synthetic polymer used to remove polyphenols and proteins, preventing chill haze and improving long-term clarity.

- Bentonite: A type of clay that removes proteins and other haze-forming particles, often used in wine and cider but applicable to beer as well.

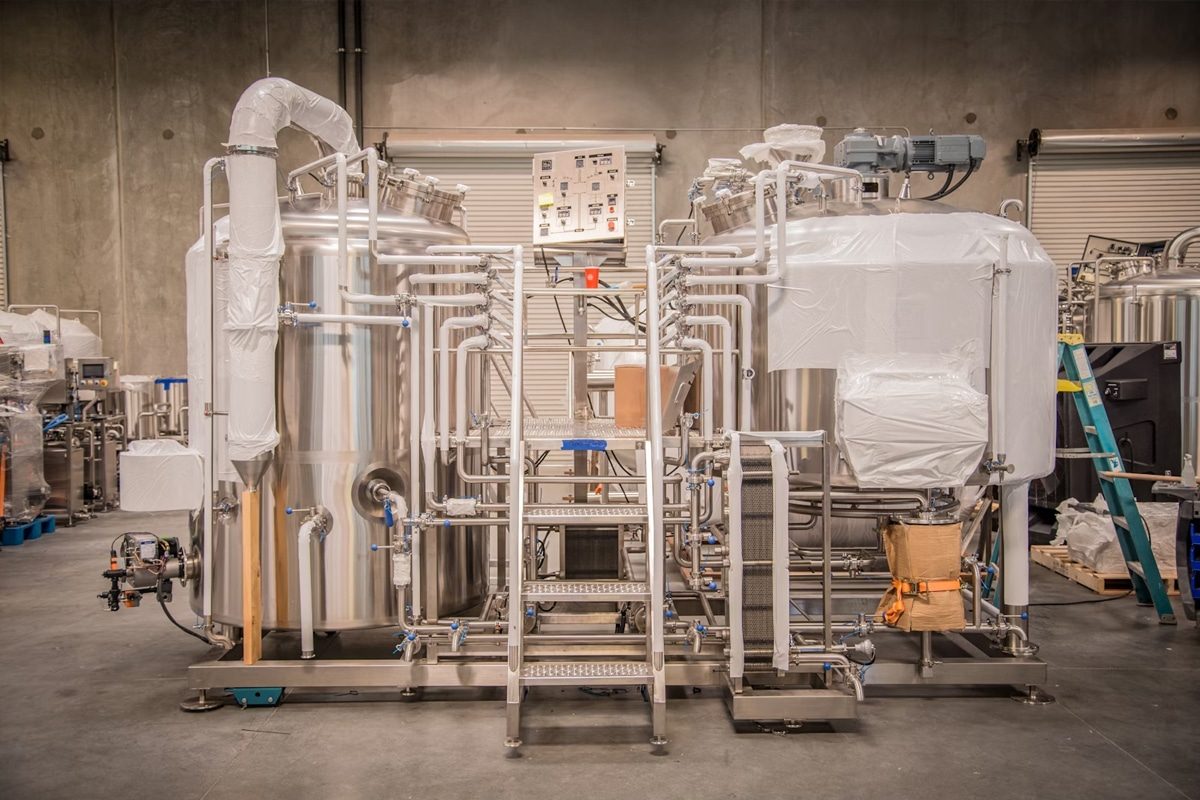

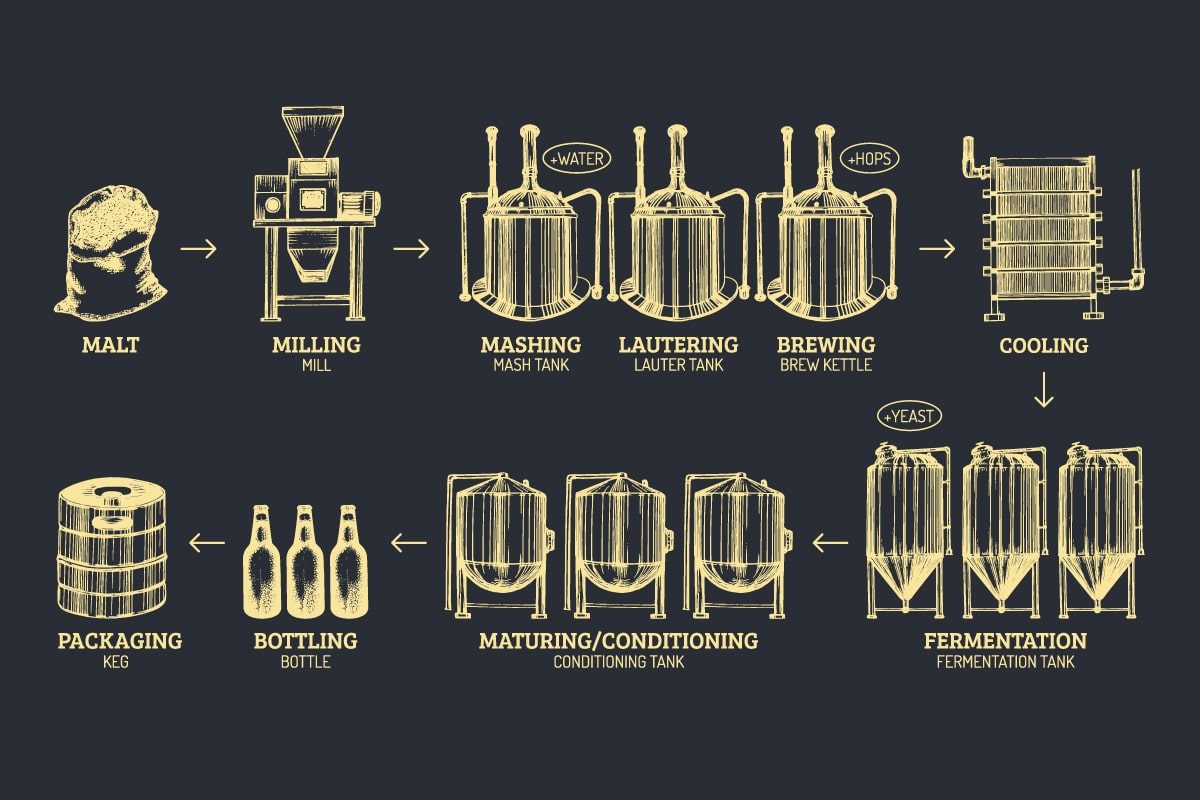

Brewing Process Overview

Mashing

Steps in Mashing

- Mashing In: The milled grains are combined with water at a specific temperature, typically between 64-68°C (147-154°F), depending on the desired beer profile. The water-to-grain ratio can help achieve the correct consistency and enzyme activity.

- Rest Period: The mash is held at the target temperature for a period, usually 60-90 minutes. During this time, enzymes like alpha-amylase and beta-amylase break down complex carbohydrates into fermentable sugars (maltose) and non-fermentable dextrins, which contribute to the beer’s body and mouthfeel.

- Mash Out: The temperature is raised to around 75°C (167°F) to stop enzymatic activity, making the mash easier to handle and prepare for the next step.

Lautering

Steps in Lautering

- Recirculation (Vorlauf): The first runnings of wort are recirculated back into the mash to clarify it by allowing the grain bed to act as a natural filter.

- Sparging: Hot water is sprayed over the grain bed to rinse out the remaining sugars. There are two main methods:

- Batch Sparging: The wort is drained completely from the lauter tun, and then the grain bed is refilled with hot water, which is then drained again.

- Fly Sparging: Hot water is continuously sprayed over the grain bed while the wort is simultaneously drained from the bottom.

- Wort Collection: The clear wort is collected in a kettle for the boiling stage.

Boiling

Steps in Boiling

- Hop Additions: Hops are added at various stages of the boil to achieve the desired bitterness, flavor, and aroma. Early additions primarily contribute to bitterness, while late additions provide flavor and aroma.

- Boil Duration: Boiling typically lasts 60-90 minutes. A vigorous boil is necessary to ensure proper isomerization of alpha acids from the hops and to drive off unwanted compounds.

- Whirlpool: After boiling, the wort is often whirled in the kettle to separate hop particles and trub (proteinaceous material). This process, called whirlpooling, helps achieve a clearer wort before fermentation.

Fermentation

Steps in Fermentation

- Pitching Yeast: Yeast is added to the cooled wort (called “pitching”) at a specific temperature, which depends on the yeast strain and beer style.

- Primary Fermentation: The yeast ferments the sugars, producing alcohol, carbon dioxide, and various flavor compounds. This stage usually lasts 1-2 weeks for ales and longer for lagers.

- Temperature Control: Maintaining the proper fermentation temperature helps with yeast health and the development of desired flavors. Ales typically ferment at 15-24°C (59-75°F), while lagers ferment at 7-13°C (45-55°F).

- Secondary Fermentation: Some beers undergo a secondary fermentation stage for additional aging and flavor development. This step can also help clarify the beer.

Conditioning

Steps in Conditioning

- Cold Conditioning (Lagering): For lagers, beer is stored at near-freezing temperatures for several weeks to several months to smooth out flavors and improve clarity.

- Carbonation: Beer can be naturally carbonated through bottle conditioning (adding a small amount of sugar before sealing) or force-carbonated in a keg using carbon dioxide.

- Maturation: Allowing the beer to sit for a period, even for ales, helps flavors meld and unwanted compounds dissipate, resulting in a more refined final product.

Packaging

Steps in Packaging

- Cleaning and Sanitizing: All packaging equipment and containers must be thoroughly cleaned and sanitized to prevent contamination.

- Filling: Beer is transferred from the conditioning vessel to bottles, cans, or kegs. Care is taken to minimize oxygen exposure, which can spoil the beer.

- Sealing: Bottles and cans are sealed with caps or lids, while kegs are pressurized and sealed with fittings.

- Labeling: Packaging is often labeled with details about the beer, such as style, ABV, and production date.

- Storage: Packaged beer is stored at appropriate temperatures to maintain freshness until it reaches the consumer.

Summary